POSSESSION OF DEPICTIONS OF MINOR ENGAGED IN SEXUALLY EXPLICIT CONDUCT

POSSESSION OF DEPICTIONS OF MINOR ENGAGED IN SEXUALLY EXPLICIT CONDUCT

Sent to court while serving time at the sex offender treatment program on McNeil Island WA

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

Violent Sexual Predator Demands State employees Records

Richard Roy Scott, convicted child rapist, and resident at the Special Commitment Center on McNeil Island, has been demanding the records of state employees. The Sexual Predator, Scott has used information in the past to harass, intimidate, and embarrass staff members. This behavior on the part of Scott the rapist is just a continuation of his predator act on children in the community. According to many of the clinical staff, the predator, Scott, will act out his sexual behaviors in any way possible, much like the alcoholic who will drink cleaning solutions when booze is not available.

The real question is why the state of Washington allows such a sick mind to have employee documents.

Worst of the worst sex offenders

Photo by Bill Wagner

A peek inside a resident's room at the Special Commitment Center showcases the college-like atmosphere center officials say they try to foster. Rooms are subject to periodic searches, but personal items and decorations that would be banned in a prison are allowed.

Saturday, January 27, 2007 11:53 PM PST

By Barbara LaBoe

McNEIL ISLAND, Wash.-- The guards have no guns at the state's Special Commitment Center for sexually violent predators -- but the people confined here are the stuff of nightmares.

The "residents" are the worst of the worst of the state's sex offenders: The ones who since 1990 judges and juries deemed too dangerous to risk releasing even after they'd served their entire prison terms.

Instead, they're civilly committed and sent here for psychiatric treatment in a hybrid facility that isn't quite a prison but nonetheless sits behind razor wire fences on an island accessible only by a Department of Corrections ferry. Without it, officials would have no choice but to set these sex offenders free.

John Wayne Thomson -- a three-time rapist now suspected in three murders in Longview, Spokane and California this summer -- was recommended for the center. So was Joseph Duncan, now accused of murder, kidnap and child rape in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, Seattle and California. But neither man -- despite predictions they'd rape again -- was considered dangerous enough to merit the Special Commitment Center.

Cowlitz County has, though, sent four men to McNeil Island. Each has a string of horrific crimes to his name, many with details too disturbing to be published.

Joel S. Reimer, 37, and Eric St. John, 27, have been formally committed and have lived at the center for several years.

Douglas A. Alsteen, 40, has been on the island since 2005, and 20-year-old James LaBaum became the fourth Cowlitz County resident there earlier this month. Both men are awaiting commitment trials to determine if they'll permanently join the 249 other men and one woman at McNeil.

Officials say most are unlikely ever to be released, because of the degree of their mental defect and their inability to control their depravity. But a handful eventually may qualify for the graduated community release mandated by the U.S. Supreme Court. The center currently has 12 men in various stages of such conditional release.

Cowlitz County's four center residents

Joel S. Reimer, 37

Sexually violated a 7-year-old boy in 1982 at age 13.

Raped and assaulted a 13-year-old boy at age 16 in 1985 -- just two weeks after being released for the previous crime.

Molested a 12-year-old girl in 1990 at age 21 -- less than a month after being released on the rape charge.

The Longview native was civilly committed to the state's Special Commitment Center in 1992 as the 10th man sent there. He was the first from Cowlitz County. He successfully sued the state, claiming he didn't receive adequate mental health treatment in the original Special Commitment Center. The center was located inside two state prisons before the opening of the current facility on McNeil Island in 2005. Won a $10,000 settlement but not his freedom.

Eric St. John, 27

Raped a 2-year-old Longview girl in 1994 when he was 14.

Molested a 10-year-old Kelso girl during the same time period. Also admitted to additional unreported offenses against children.

Amassed numerous parole violations for having children's clothes, toys, pornography and other items in violation of his sex offender treatment.

Arrested for failing to register as a sex offender in 1998 in Asotin County in Southeast Washington. Also tried repeatedly to volunteer with the Boy Scouts and briefly had a job in a McDonald's playland in Asotin County by concealing his convictions.

Civil commitment papers were filed in 1999 due to the 1998 "recent overt acts" in Asotin County. He was subsequently committed and remains on McNeil Island.

Douglas A. Alsteen, 40

Raped a 10-year-old Kelso girl in 1985 at the age of 19.

Pleaded guilty to attempted rape near Castle Rock in 1990 -- at age 23 -- after threatening a woman with a gun, hitting her and telling her he would rape her. Also pleaded guilty to physically assaulting two other women in Kelso with sexual motivation.

Had "numerous infractions of a sexual nature" while incarcerated, according to court records.

Has been at Special Commitment Center since 2005 awaiting a civil commitment trial that had been scheduled to begin Monday but was postponed until June.

James LaBaum, 20

Sexually violated a wheelchair-bound 14-year-old boy in Longview at the age of 12 in 1999.

Attempted to rape a 7-year-old girl in 2001 at the age of 15.

Has had numerous sexual infractions while incarcerated, including touching other inmates, threatening sexual assault and acting out sexually in front of others, according to court records.

Transferred to McNeil Island on Jan. 15 and awaiting a civil commitment hearing, though he's refused a lawyer and told the judge he wants to be committed.

Source: Civil commitment court records

Until then, officials say keeping the residents on the restricted Puget Sound island keeps everyone safer -- including the residents themselves.

"I can't tell you the prevalence of crimes that would occur if they all were released," said center Superintendent Dr. Henry Richards. "But I do know a large number of crimes are not being committed because the people are here."

Not prisoners, not free

The Special Commitment Center has rows of jagged razor wire, 190 surveillance cameras and metal doors that clang shut with an eerie finality. But state officials are quick to point out that it's not legally considered a prison.

The center is run by the state Department of Social and Human Services -- not the state Department of Corrections. Its security personnel are considered rehabilitation counselors and don't carry guns. Residents wear street clothes, decorate their rooms like college dorms and -- for the most part -- amble at will between their rooms, common areas and even an outside courtyard.

And, unlike prison, none of sex offenders at McNiel have a release date. They remain on the island indefinitely until they're deemed cured. And past history shows most will never be cured.

Officials say the current center -- the latest of several locations -- is designed to augment treatment and to comply with U.S. Supreme Court rulings that the center is only legal if it's a legitimate treatment center.

Created by the Legislature in 1989, the center was initially located inside state prisons but had too much of correctional institution feel -- a fact detractors were quick to point out.

Accordingly, it is now housed in a former federal prison renovated in 2005 to resemble a community college campus, complete with units named Cedar, Redwood and Gingko and buildings washed in Northwest hues of salmon, ocher and hunter green.

"We try to provide a lot softer environment than a prison," said Kelly Cunningham, one of the center's operational managers, as men milled around the outside quad, checking their mail, smoking and gossiping. "And we're always struggling with respecting the fact that residents have more rights than inmates but also maintaining safety and security."

The residents' status as patients rather than prisoners grants rights not afforded in prisons.

The two halfway houses -- one on the island and the other in Seattle -- provide even more freedoms, including holding outside jobs and trips to the mall, albeit in the company of around-the-clock escorts and electronic monitoring. Five of the 18 men granted conditional release have been returned to the SCC for program violations -- one is awaiting a hearing -- but none have been known to reoffend.

Residents must establish a history of good conduct in the center, participate in extensive therapy and undergo a battery of tests and evaluations before center officials recommend them for conditional release. They also must go back to court and convince a judge they're safe to be let out.

Still, it's a constant uphill battle to gain public acceptance when any of the center's residents are released, Richards said.

"I think the perception is we should be running it like a prison even though it's not," he said. "So we provide treatment and an opportunity to leave in the face of the reality that society does not want these people to return."

No cooperation, no release

Despite the more open atmosphere officials try to instill at the center, critics such as Vancouver defense attorney James Mayhew maintain treatment behind locked doors is more prison than hospital. And he says keeping the residents here against their will illegally punishes them twice for the same crime.

"The law says civil commitment is indeterminate until they're rehabilitated, treated or whatever word you want to use," said Mayhew, who is defending Alsteen at his Cowlitz County commitment trial. "But it's basically a life sentence."

Some residents agree.

"I'm here for something I might do, not for something I did, and I think that's completely wrong," said Anthony Rushton, a 33-year-old Spokane rapist who has been civilly committed since 1999. "This law was created out of spite."

Rushton raped a child as a juvenile and then, at age 20, raped a 17-year-old girl and attempted to rape an 18-year-old woman in a two week period.

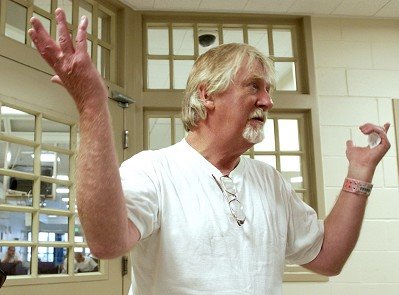

"If this is a treatment center then why has no one ever really graduated (to total freedom)?" asks gray-haired Richard Scott in a well-rehearsed spiel that officials say is delivered to any reporter who tours the facility. The child rapist has been at SCC for three and half years but refuses treatment, calling it a scam. "This is a prison."

Superintendent Richards likens the center -- and it's so-called graduation rate -- to a cardiologist who handles the most life-threatening cases of heart failure.

"If the worst patients aren't talking to their doctor and not taking their medicine, how many do you think would be alive in 10 years?" he asks. "Here we work with the most pathological sex offenders, and many have lawyers telling them not to talk to us. ... We can treat them, but the motivation to participate in treatment is harder won."

He also adds that some residents seem to prefer the safety of the center compared to the risks of reoffending or facing a vengeful public. The targeting and killing of two sex offenders in Bellingham last year rocked many residents, Richards said. (The men killed were not SCC residents).

"After that, a lot of (residents) were saying 'Why should I go back out there?'" Richards said. "So we have to encourage a lot of them that this is not a retirement center."

A land of pedophiles

Many residents scorn treatment altogether -- either to protest the center or because they don't want to confront their own demons.

Center officials say they can't force residents to attend individual or group therapy sessions. Overall, about 50 percent of residents attend treatment. The percentage jumps to 70 percent among those who have been formally committed.

Those awaiting their commitment trials, like Alsteen and LaBaum, often refuse treatment because they fear the total disclosure required in the sessions will hurt their chances in court, said Richards.

Sex offenders "qualify" for civil commitment based on a psychiatrist's finding that they're more than 50 percent likely to reoffend in a violent, predatory manner. They're transferred to McNeil Island at that point, but it's not until a jury rules that they do meet the standard that they're formally committed.

Cowlitz County's four SCC residents were not available for interviews during a tour of the facility. Because of their mental health status and some ongoing legal claims, officials can't require any resident to consent to an interview.

Sex offenders can be treated with behavior-modification therapies, Richards said, but those on McNeil Island have such severe problems that they're far more likely to reoffend. About 62 percent are pedophiles, according to center officials.

Despite the odds against a complete cure, some residents praise the treatment even while chafing at once again being locked away from society.

Rolando Aguilar was the second man sent to the center in 1990 and the first to be officially committed. He admits he'd like to be free and called the center a Nazi concentration camp in a 1993 interview. But Aguilar adds that if he hadn't been made to face his crimes and disorders he would have raped again.

"I could be in here all day feeling pity for myself ... but we also have to look at what we've done and the lives we have destroyed," the 46-year-old said of therapy at the center. He hopes to one day leave the facility, but only when he's sure he'll be safe back in society.

"I don't want to get out just to not be locked up," he said. "And I don't want to create any more victims."

Big-dollar answer

One day the state may no longer need McNeil Island though that day is still decades away.

Public demands to get tough on repeat sex offenders led to the center's creation, and lawmakers also substantially lengthened sentences to keep sex offenders in prison longer. They also created a "two strikes" law for sex crimes in 1996 that carries a mandatory life sentence.

"The two strikes law may eventually reduce our population here," said Steve Williams, the DSHS spokesman for the center.

That would be good news for the state's pocketbook, because the SCC, complete with intensive treatment, 24-hour escorts at its halfway houses and electronic monitoring, doesn't come cheap.

It costs roughly $160,000 annually to house someone at the SCC. At the halfway houses the costs are between $250,000 and $500,000 per man each year. A prison inmate, by comparison, costs the Department of Corrections about $27,000 a year.

The state will be paying those higher costs for years to come because the new sentencing laws aren't retroactive and each year brings a new batch of candidates.

On average, prison officials recommend 26 soon-to-be released inmates annually for civil commitment. Roughly 15 of the recommended prisoners proceed to commitment trials while the remaining 11 are set free because they don't qualify. Of the cases that go to trial, almost all result in a permanent stay on McNeil Island.

"We rarely lose," Todd Bowers, assistant attorney general in the state's Sexually Violent Predators Unit, said this summer. "In 16 years we've lost five cases."

That means statistically that Alsteen and LaBaum are likely to be committed and remain on McNeil Island. Likewise, it's likely Reimer and St. John also won't ever walk free.

"It will be hard for most (residents) to successfully work the programs," Richards said. "These are people with severe disorders."

Rushton, though, would leave tomorrow if he could.

He can't guarantee he'll never rape again, but he said therapy has helped him to control his anger problems and recognize his risk factors. Beyond that, he said a transition back into society should be the next step -- not an indefinite stay on the island.

"I can understand the fear," he said. "But we're also human."

Copyright © 2009, The Daily News All rights reserved.

Post a Comment